A couple of summers ago Luciano and I watched, in rapt attention and mouths open, the dramatic finals of the National Spelling Bee Competition.

These children, most of whom were not old enough to know that a hallux is the innermost digit of the hind limb, (otherwise known as the big toe) had to spell such words in front of an audience of, oh let’s say, six million people.

There was such excitement that at one point a child fainted dead away into the stage backdrop, only to spring back to his feet, ready to tackle alopecoid, a word meaning crazy like a fox, or something like that. He should have gone down at gyromancy, a word that means “divination in which one walking in or around a circle falls down from dizziness and prognosticates from the place of the fall.” I am not making this up. These words and definitions come from the official website.

Spelling Bees are a ridiculous concept to Italians. In fact, our friends laugh when we describe them. There is good reason for their disbelief, beyond the histrionics of putting a child under such pressure. For Italian words are spelled exactly as they are pronounced. There would be absolutely no sport in an Italian spelling bee and there is a considerable amount of pride in that simplicity.

Italians get into trouble when they try to apply this logic to English. How on earth could anyone imagine that the “o” sound can be spelled “ough” as in though, “ow” as in throw, and “oa” as in boat? I spend my days apologizing for the irrationality of my mother tongue, while at the same time drilling it into their minds.

Giancarlo came to lunch sputtering with anger one afternoon.

“How can a civilized country like America spell the sound “f” with a “ph”? It should be spelled Filadelfia!”

I think someone made fun of his pronouncing the name of that city in Pennsylvania as Piladelpia. It wasn’t me.

English spelling is in fact such a crap shoot that students of the language often give up trying to learn by reading, but succeed in memorizing songs and movies. Nine-year-old Julia can sing, word for word, a very complex song of unrequited love by Hilary Duff. She understands nothing, but her pronunciation is spot on. Luciano learned his sparkling American elocution by watching movies, Pretty Woman in particular. While he speaks better English than Richard Gere, for both Italians, the written word is sometimes a mystery.

“The rules are so hafarzard, Serena,” Luciano complained.

“The rules are what?”

“Hafazard…or is it haphazard?”

“Completely.”

The pesky “ph” strikes again.

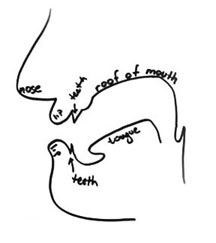

One of my students told me the story of his childhood English teacher. This gentleman, a former Italian soldier, learned all his English while being held in a POW camp in Mississippi during World War II. During the English lesson one day a special guest arrived to help out with pronunciation. The guest, a former soldier horribly wounded in battle, had lost a part of his face. In order to protect the wound, doctors had placed a membrane over the missing part of his jaw and cheek. Someone had figured out that by placing a small light in the uninjured part of his mouth, his tongue could be thrown in silhouette through the membrane, thus providing a perfect demonstration of exactly where the tongue should be when, for example, saying the word “mother” as opposed to “thumb”. The poignancy of this image is almost too much to bear: Prisoners, in order to learn the very language of their captors, peering intently at an American soldier, patiently holding his tongue in position through a wound very possibly inflicted by his audience’s countrymen. Yet, my student told me this story with childish glee, absolutely delighted at the American ingenuity.

Back at the Spelling Bee, the line-up of hopeful children square their shoulders, ready to crack the mysteries of English spelling. In fact, we are lucky to have them around to keep the language so absurdly rich. Otherwise, we mite bee riting light as lite or the word hebephrenia with an “f”, of all things!

The spotlight falls on a twelve-year old. She closes her eyes to concentrate. All of America holds its breath as she, at that moment, single-handedly protects our orthographic foolishness. Could you use it in a sentence please?

Hebephrenia “a form of schizophrenia that is a characterized by silliness, delusions, hallucinations and regression that has an early insidious onset.”

Anna Maria went out to the gate to greet the mailman. Holding up the virtually blank envelope he asked Anna Maria, “It comes from America. Do you think this goes here?” He jerked his head in the direction of our house.

She took it from him and squinted at the faint wash of ink across the surface. She could just make out the careful, round handwriting.

“Yes, yes. It must be. I think it is from her mother”

“Hah! I think the mailman swam across the ocean with it in his teeth!” With that he turned and roared off on his scooter, his head back, laughing.

The envelope is small and battered, but is now completely dry. If you look closely, you can just make out the word “Maren”… and then down a line, “Italy”. The rest is a faint veil of blue, the ink washed away somewhere between Virginia and Mareno di Piave. And yet it is here, sitting on our kitchen table. The contents have disappeared as well. I think my mother was writing of memories, but I am not sure. The words are gone, but it does not really matter.

Life in a small town is a delicate balance. I know that the lady down the street with the life-sized, plastic blue-eyed dog in the front yard is the mother of the town vet. And she knows that I am the recent bride of the boy down the road whose name she can never remember. She greets me warmly and asks after the family each time I run past her door. Every time. She probably knows my running time better than I do. I am waiting for her to start giving me breathing tips. The butcher reminds me when it is time to order my Thanksgiving turkey. Being the only American in town, it is easy for him to remember. Each time he asks how I cook a whole turkey and after I explain, shakes his head and says, “One day I will try it.” The complete turkey as usual, continues to be a mystery to Italians and never fails to get a huge reaction.

I ventured into the Mareno bakery where I spoke to a very nice young woman. I am not convinced that it is any better than the bread from the supermarket, but when I mentioned that I had been in there, Luciano said, “Oh, yes. I wanted to ask that girl out once.” I made a mental note to reevaluate the bakery situation, but being pretty sure of having my hooks firmly in Luciano, I can only feel smug should I go again into that bakery. And I will. It is the only one in town.

I can be sure that the ladies at the meat counter in Mio market know that I prefer the spicy ossocollo and not the fatty one. I know that the Antonella at the drycleaners likes to practice her English on me and will be able to put her hands on my stuff even when I have lost my ticket. I also know that I cannot go to the market in my sweatpants because I know most certainly, and only then, I will run into one of Luciano’s cousins. While Anna the beautician is waxing my legs, she will give me a message for Anna Maria.

For several years Luciano had regularly corresponded with a girl. Then the letters stopped. A few years later the mailman, who at the time was a very grumpy gentleman, made a point of personally delivering a letter.

He placed the envelope in Luciano’s hands and muttered, “She hasn’t written for a while.”